Discussion

Imaging Parameters Optimization

If all you wanted to do was to maximize the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) of your images, then you would increase the exposure time and/or light intensity until the histogram was as close as possible to the upper limit of its domain without saturating any pixels.

But what if the intensity is maxed out and you still have room left in the histogram to improve the SNR? You could increase the exposure time still further. But, as a result, doing so would decrease your frame rate. If you also needed to image fast dynamics within the cell, and these required a minimum frame rate, then there would be an upper limit to the value for the exposure time that you could set. Beyond this value, you would not have a high enough frame rate to see the thing that you would like to see; it would be blurred out.

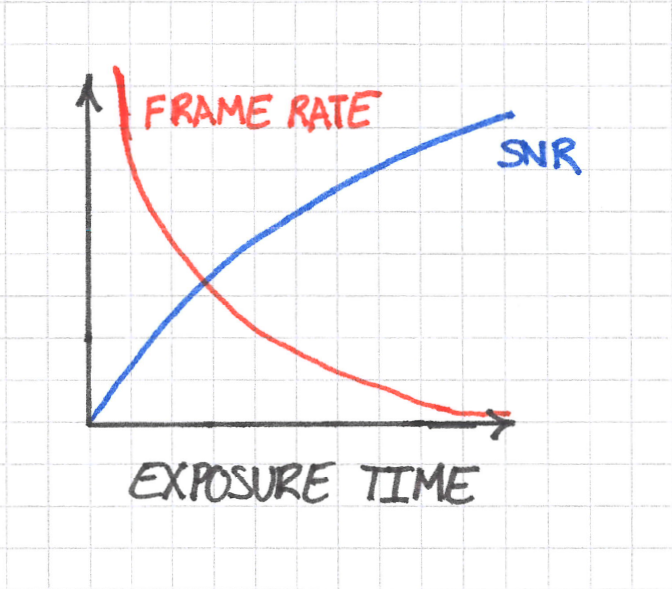

Ultimately this means that you must sacrifice some SNR to obtain a sufficient temporal resolution. We can visualize the problem like this:

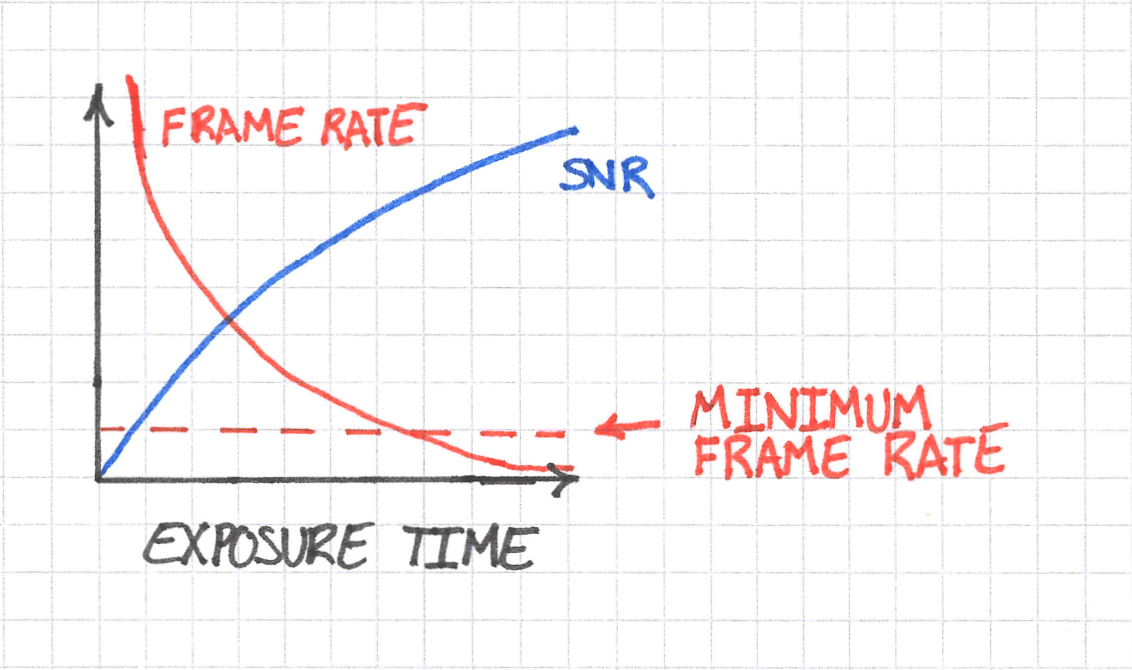

Do not worry too much about the exact shapes of the curves in the sketch above; what’s important are the trends. SNR increases with exposure time, whereas frame rate decreases. The dynamics that you want to see impose a requirement on the minimum frame rate at which you can image. You can imagine this minimum as follows:

But the minimum frame rate also imposes a maximum on the exposure time. This value is just the vertical line through the point of intersection of the frame rate curve and its minimum required value.

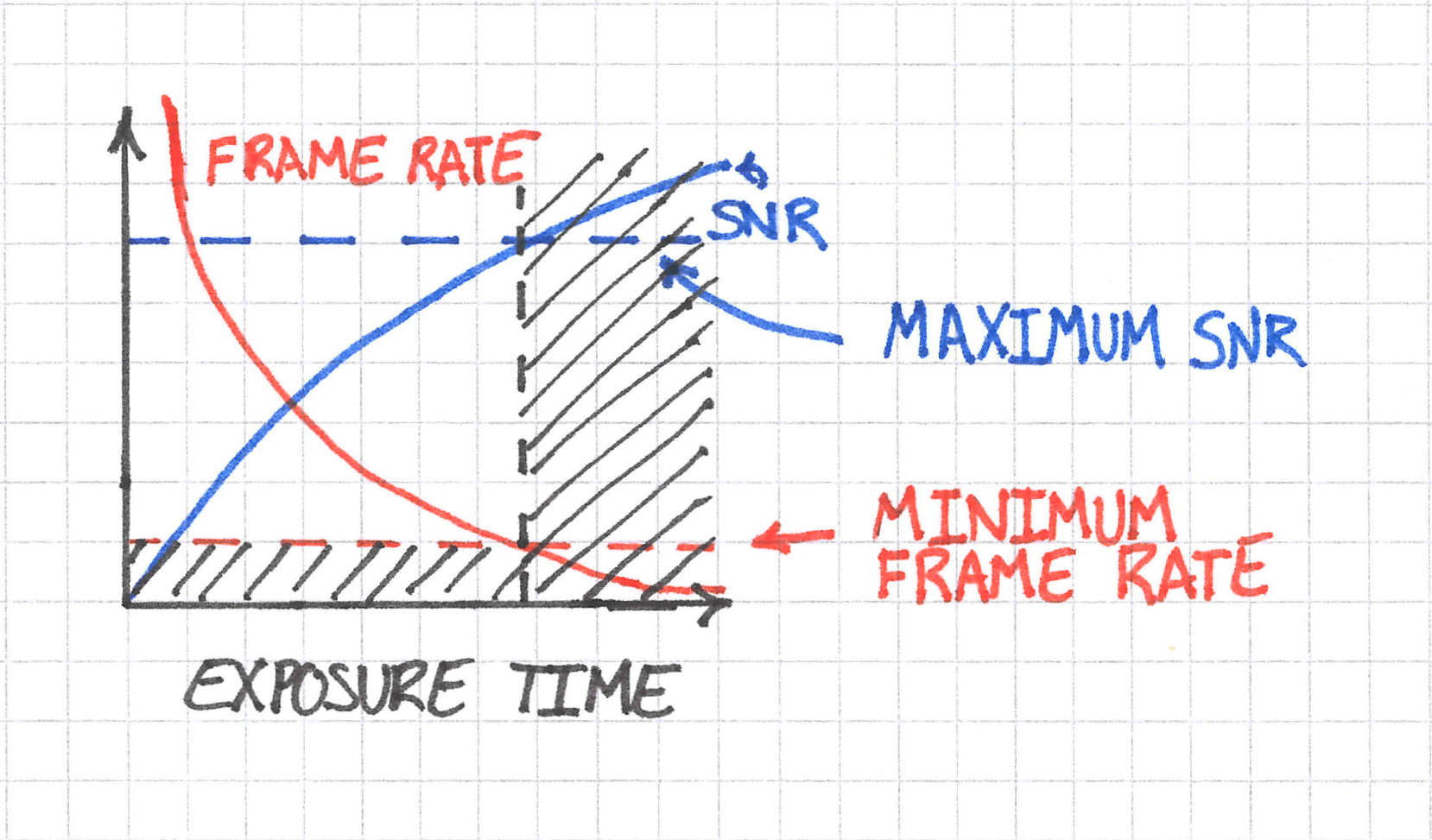

Taking this logic one step further, the maximum exposure time also imposes a maximum achieveable SNR, so in the end we have something like this:

The frame rate requirement ends up reducing the parameter space of exposure time and, subsequently, the maximum achieveable SNR.

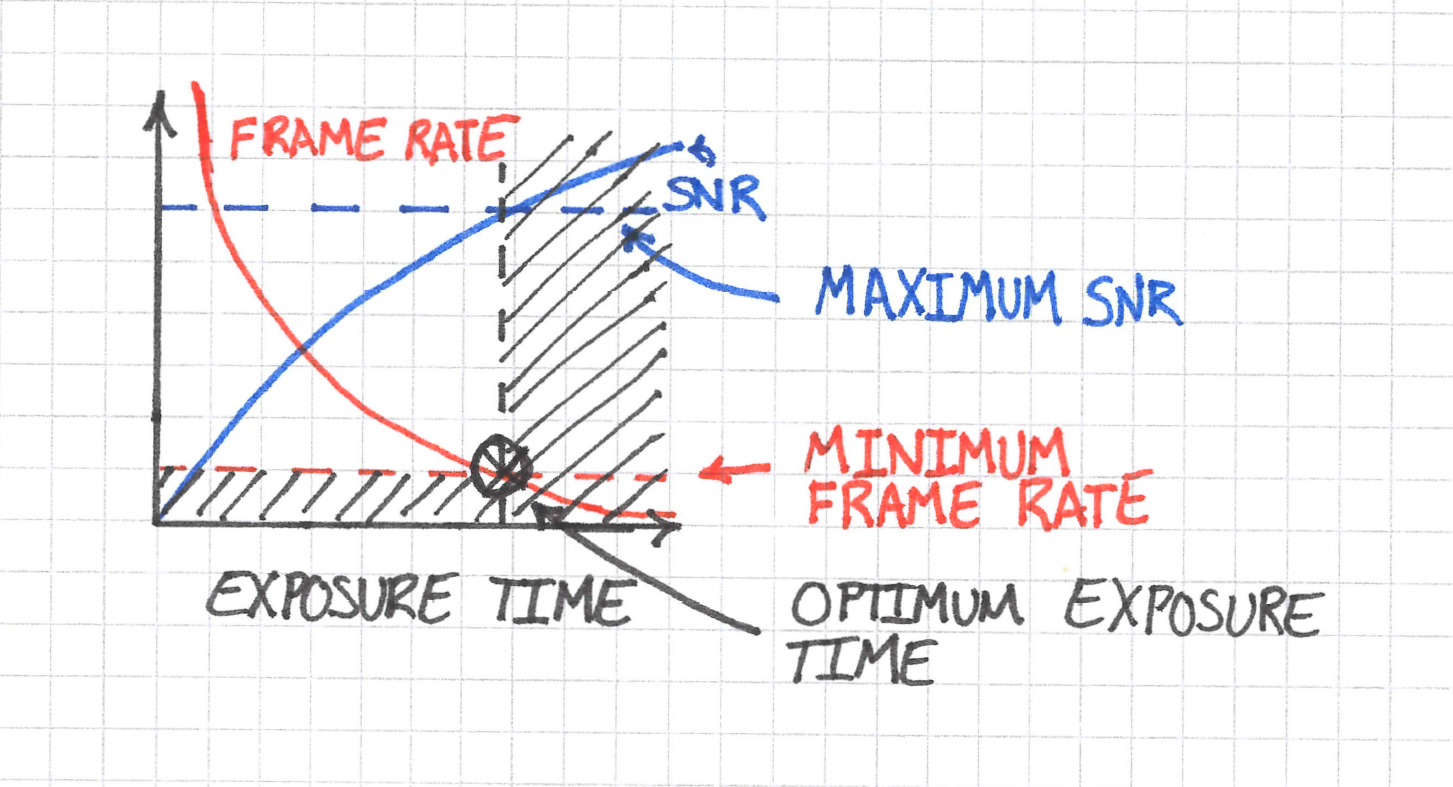

We have finally arrived at an optimization problem: given the frame rate requirement, what exposure time maximizes SNR?

The answer in this case is straightforward: it’s the exposure time where the frame rate is just fast enough to see the dynamics that you are after.

You can of course image at shorter exposure times, but then your SNR will suffer.

I think it’s worth making explicit the logic in this example because it’s central to how one should think about performing imaging experiments:

- First we identified our requirements (the timescale of the cell’s dynamics).

- Next, we turned the problem into an optimization problem. We decided to maximize SNR (a quality of the images) by tuning the exposure time (a property of the microscope).

- We then solved for the exposure time that maximized the SNR.

But What Parameter Values should I Choose?

The above discussion is fine from a theoretical perspective, but you’re probably wondering how to set the actual value of the exposure time when at the microscope. Or, for that matter, how do you actually set any microscope property? After all, you’re not going to have the nice simple plots that I drew above when making your decision. Rather, you’re going to have only what you see in the images.

This is where imaging becomes a bit more art than science. Regardless, we can still approach the problem systematically.

Feasibility

First, I recommend that you think broadly about what you’re imaging to set some bounds. A cell biologist looks at organelles, and from experience we know that these move on the order of milliseconds to tens of seconds. A developmental biologist studying embryo development, on the other hand, cares about timescales that are probably more on the range of hours to days. In these cases, you can conclude that frame rates are probably going to be somewhere between 1 and 10,000 frames per second (fps) for the cell biologist and much slower for the developmental biologist.

With bounds established, you should next consider your requirements and constraints. CMOS cameras have exposure times anywhere between fractions of a millisecond to tens of seconds. If you want to study something faster than the camera can image, then you’ll need a different approach entirely.

Parameter Tuning

After having decided that your experiment is at least feasible, you’ll need to develop a sense for what makes a “good” image dataset.

One quality of good images is that they have high SNR. But how do you estimate SNR? By using the image histograms. As previously mentioned, a good SNR means the center of the distribution of pixel values in the histogram is as close as possible to its upper limit without saturating pixels. But keep in mind that this is not the same as measuring the SNR directly. So you will have to develop a feel for how to estimate image qualities indirectly from images and their histograms.

Another quality of good images is that they satisfy your requirements. Do you image fast enough to see the thing that you want to study? How do you know what frame rate is required if you haven’t looked yet? Here pilot experiments can help. You can try a range of exposure times and frame intervals on test samples and see roughly what range of values works. You may not arrive at exact values, but you can at least establish a rough order of magnitude.

Back of the envelope calculations help to pinpoint ranges of parameter values in some scenarios. For example, in tracking experiments, if you know the density of particles and their diffusion constants, then you can work out what frame rate is necessary to capture a certain number of frames before a collision occurs with another particle.

What Else can I Adjust in my Experiments?

It’s not only microscope parameters that can be tuned. Signal-to-background ratio (SBR), which I discuss in the next section, can be improved through better sample preparation or a change of microscope. A switch from widefield to confocal microscope can help in this scenario in particular. Try to identify what aspect of the experiment is preventing you from answering your hypotheses, and then look at what can be changed to make it possible.

What about Photobleaching, Phototoxicity, Spatial Resolution, and Signal-to-Background Ratio?

I deliberately left these out of the discussion above to keep it simple, but they need to be considered as well. Phototoxicity and photobleaching ultimately limit the laser intensity (which in turn limits the SNR) and the length of your experiments. You won’t be able to avoid these effects entirely.

Spatial resolution is harder to adjust through microscope parameters alone since it depends heavily on the microscopy method itself. Still, improving SNR does slightly improve spatial resolution, and choice of microscope is just as important as anything else when designing an imaging experiment. Likewise for signal-to-background ratio. Lightsheet microscopes have become so popular because they efficiently solve the issues relating to SBR.

The key is to establish the requirements for your experiments in terms of these qualities:

- spatial resolution

- temporal resolution

- SNR

- SBR

- phototoxicity

and these constraints:

- budget

- time available

- equipment available

- expertise

I’m going to say it again because it’s so important: without any requirements or constraints, there is no way of doing meaningful, quantitative experiments on a microscope because there is nothing to optimize.

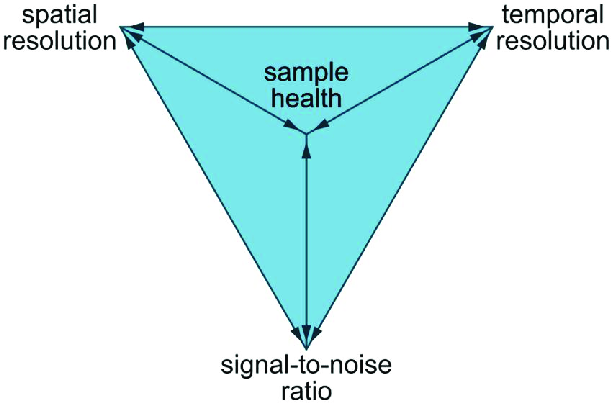

Polyhedra of Democracy

You might have heard of the “triangle of frustration”, “pyramid of compromise,” or similar terms. One such example looks like this (source):

The idea here is that you can move about within the pyramid by adjusting imaging parameters, the microscopy method, the sample preparation protocol, and more. In doing so, you improve on one of the qualities at the vertexes of the pyramid but necessarily sacrifice something at the other vertexes. Improving spatial resolution, for example, might mean decreasing temporal resolution and cell health.

Again, it’s very hard to put the imaging problem on firm, algorithmic grounds with definite data. This is partly because we can’t measure everything we need to (how do you quantify phototoxicity?), partly because it’s not always clear what makes for an optimum set of parameter values. Still, these concepts help you navigate the challenges inherent in optimizing your imaging experiments by

- making clear what the tradeoffs are, and

- helping design pilot experiments that help narrow in on the right range of microscope parameter values.